Build Your Business On Curiosity

April 12, 2023

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

In this episode, Jeff quizzes Dan about his unique journey—from being a curious child engaging with adults, to becoming the trusted coach to some of the world’s most successful entrepreneurs. They discuss the power of asking questions, the complexities of adulthood, and how your early experiences might just shape your whole career. Entrepreneurs and creatives alike will gain valuable insights from Dan’s business coaching expertise and Jeff Madoff’s experience in producing a hit musical.

Show Notes:

- Dan Sullivan’s childhood was filled with conversations with adults, which helped him develop a unique skill-set and perspective.

- His parents were keen conversationalists, and he believes they both had ADD, which contributed to their love of engaging in discussions.

- He found that adults didn’t always have answers, and that asking questions was a powerful tool for understanding their experiences.

- Dan’s love of reading and encyclopedias helped him dive deeper into the topics he discussed with adults.

- He realized early on that being an adult was complicated and that many people didn’t ask themselves the questions he was asking them.

- During his Outward Bound expedition in the UK, Dan kept a journal, in which he wrote about the importance of understanding your experiences.

- Dan’s journey took him from farm country in Ohio, to a job with the FBI, then a move into advertising, and eventually to founding Strategic Coach.

- Jeff Madoff shares his excitement about his musical, Personality, moving to The Studebaker Theater in Chicago for the summer of 2023.

- At the Parsons Design School, Jeff got to teach a student a valuable lessons: Skip the excuses.

- Jeff and Dan distinguish the differences between courage, self-esteem, and confidence.

- How do you measure when your company actually started?

- The key factors of Dan’s success are asking people open-ended questions, distilling and depersonalizing their experiences, then presenting them back as universal principles.

- The only way to grow and develop, Dan believes, is to take ownership of your experiences and learn from them.

- Showdown: Adam Smith versus Karl Marx.

- Many successful entrepreneurs let their money outstrip their meaning. Avoiding the fear of failure, they also miss out on excitement and the opportunity to grow.

- There’s a lot of money out there looking for a purpose.

- You have to be in motion to be happy.

Resources:

Jeff Madoff: https://acreativecareer.com and https://madoffproductions.com

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach: https://strategiccoach.com

The Parsons School of Design at The New School, New York: https://www.newschool.edu/parsons/

Personality, at The Studebaker Theater, running from June to September, 2023: https://www.fineartsbuilding.com/events/personality/

The Studebaker Theater in Chicago’s Fine Arts Building: https://www.fineartsbuilding.com/

Episode Transcript

Jeff Madoff: I’m here with my friend Dan Sullivan, and it’s always hard for me to then just pause, ’cause once Dan and I start talking, it’s off to the races, and we talk about anything and everything.

So welcome to the podcast. And Dan, it’s great to see you today.

Dan Sullivan: And I was just thinking, I don’t know why, but ever since I woke up this morning that 2023 is a year that’s gonna have a big personality.

Jeff Madoff: Thank you very much. And there you have marketing, ladies and gentlemen.

Dan Sullivan: And yeah, yeah. Halfway through the year, we’ll be off and running. Then Chicago. You will be, yeah.

Jeff Madoff: And that’s right. That’s right. And I’m really excited about that.

You know, Dan, when we’ve talked before, and you’ve talked about your childhood, you told me one of the things that you used to really enjoy doing when you were a kid was engaging with adults and talking to them. How did that come about? Because most kids didn’t talk to adults ’cause the adults were their parents’ age and children weren’t to be engaging in that way. But you did that and you derived enjoyment from that. What made that attractive to you, and or what did you get from it?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I mean the timing is kind of blurry, but the big thing is that my parents were conversationalists. I think that both of them were ADD, so the chance to have a conversation was a distraction from anything that they had to do that day. And that’s kind of one of the ADD characteristics I’ve inherited. It’s an inheritable, apparently, it’s a, one of the more inheritable personality traits, psychological traits, that you can have is being highly distractible, being interested in a lot of different things.

So I think that it must have started early with my parents. But then there was a birth order that favored me, or it was something that happened to me that I turned into a an advantage and that is that I’m the fifth child in the family, and there’s a big gap between me and the next older, and the next olders were all off to school by the time I hit five or six years old. So I wasn’t left alone at any time, so I was either going someplace with my mother or someplace with my father. And this is all northern Ohio, not too far from where you were born, but farm country, Ohio.

Cedar Point is a big place on the map and even bigger today than it was when I was growing up, but it’s one of the major amusement parks in the US, but it’s one of the great roller-coaster parks, and they have a corporation now that owns the next five, I think, in the United States, so the top six are owned by the Cedar Point Corporation.

So my mother belonged to, I would say social organizations where she would volunteer, and my father was around buying farm equipment or buying farm implements and fertilizer and seed and everything that was needed for farming while my older, the four older ones, were at school. So I went along, and I was dealing with adults all day, you know, I was meeting adults all day.

And something, I think it’s probably innate, something happened where I just started asking questions about the experiences of the the adults that I was meeting and all of them either had First World War experience or they had Spanish Flu epidemic experiences, or the Roaring Twenties when you know, a lot of electrical things became part of life like radio, television—not television, but radio. People got phones, and there was tractors, and you know. So it was sort of a real modernization period in American history for the farm cultures.

But then they had the Great Depression experience. They had the Second World War experience, and here we were, I’m talking about now ’49 or ’50. Nineteen forty-nine or ’50, and I just had this way of just asking them pretty open-ended questions about their experiences of growing up.

And a couple of things came across to me which have lasted for a lifetime, and I think it probably explains why we hit it off pretty quickly when we first met, is that I found that they didn’t really know their experiences until somebody asked them about them. That they were very pleased to be involved in the conversation, especially with someone who is very young, and that you could keep them going for quite a long period of time if you just listen to what they said and then ask them about the thing that they had just said.

So this was a well-developed experience. This was a well-developed skill and a well-developed habit before I got to first grade. And when I got to first grade, the only ones I could talk to were actually the teachers, ’cause they were comparable age, you know, and the adults who were in the school. So I missed the train to hanging out with childhood friends. I got hooked on this adult train, and that’s pretty well been my whole life.

Jeff Madoff: And not only has it been your whole life.

Dan Sullivan: It’s it’s my business.

Jeff Madoff: That’s right. And that’s what I think is so interesting is that what you’re doing, I would posit it’s an iterative process from what you did when you were a kid, and what you enjoyed doing when you were a kid. Would you say that’s accurate?

Dan Sullivan: Oh yeah, yeah. And then I was a reader. My mother really pushed reading. But I I don’t think I learned early. I think I learned, like everybody else did in first grade. But I really took to it.

Encyclopedias. You could really go a long way with encyclopedias, ’cause I could listen to a conversation and then look it up and encyclopedia. And we were far away enough from those events, especially the Second World War, that there was a lot about it now that you could look up, and “So-and-so, they were in France,” and you could look up where they were in France or they were in the South Pacific. And I just felt that this was a vast, limitless world, this experience.

And one other thing I should say, Jeff, it struck me very early that being an adult was very complicated.

Jeff Madoff: Tell me what you mean by that.

Dan Sullivan: Well, they didn’t have answers. They didn’t really have answers. And you could tell the more you asked them about your experiences, that, in a certain sense, you had the upper hand here because these are not questions they had asked themselves.

Jeff Madoff: OK.

Dan Sullivan: And that’s the other thing: I found that questions were incredibly powerful.

Jeff Madoff: So when asking those questions, you know it’s interesting, you had your sojourn into advertising. But you ended up going back to something, and I don’t know, were you aware of it when you started Strategic Coach? Were you aware that in fact what you were doing was something that one may have said is your true calling? Or was it just—I don’t think anything’s happenstance. So like, I guess I can’t ask it that way. But were you aware of that connection? Did you put that together, or not until you were asked certain questions?

Dan Sullivan: I don’t know. My answer to the question is I didn’t really know because, you know, I moved from a job, a paid job in an advertising agency to being out in the marketplace by myself. And I just had the feeling that cash-flow is such a huge constant in your life, that you would just get the next job, you would get the next engagement and everything.

But I will say this, that when I was 20, I’d gone to the UK, to Britain, and I went to a outdoor program, which is called Outward Bound, that if you read the history on it, was created by Prince Philip, and it was a sense that after the Second World War there was sort of like an anti-war anti-military, anti-boys-being-men, movement in the UK, because they were on the winning side, but they were probably one of the biggest losers, because the US gave them massive amounts of help to everybody, but they didn’t give all that much help to the British. There’s always been this friction between the British and the Americans, you know.

So there was this feeling then among war veterans in Great Britain, Prince Phillip being one of them, that they needed some sort of program that challenged them physically, that they wouldn’t be a wartime danger thing, but it would be physically confronting. And they had a program which was part of the time climbing in the Scottish mountain ranges in Scotland and then sailing on the North Sea. And I signed up for it.

I’d been part-time in college and I had had a job right out of high school with the FBI—actually worked in the FBI right where the mall is in Washington, DC, just maybe three blocks from the Capitol. You know, and I was looking up files on Communist Party USA, and what you were getting was actually reports after reports after reports of FBI informers, who, if all of them had not paid their dues, Communist Party dues that year, the Communist Party would have collapsed in the United States. It was only being held in place by the dues of all the informers. They themselves did not know that the people that they were informing on were FBI informers. So the FBI’s had a very interesting wayward history.

But I had that job for a year and a half, and then I quit. I had saved enough money because I’d wanted to do this Outward Bound thing, and I went off and I did it, and it was a very satisfying, very successful experience in terms of my goals. But I kept a diary and I remember writing something in the diary that relates directly to your question. It was, and I think that the educational system as I’ve experienced, is all pointless except for some basic skills in the sense that what we should be learning most from is understanding the importance of our experiences and actually deriving lessons, like almost structured lessons, from our own experiences. And my sense is that the, what later became the Strategic Coach really started with the diary entries that I did on that trip.

So I was 20 then and I started Strategic Coach when I was 30.

Jeff Madoff: So what would you say that… Because I’m hesitating, because there’s two directions that we’ve gone, which I think are really quite fascinating.

I’ve mentioned at times that it’s not unlike therapy in the sense that you’re asking questions that people don’t usually ask themselves, which can create… You’re not giving them answers, you know, you’re questioning them, they’re giving the answers or finding the answers, which is what a good therapist does is just, you know, hope that you can hear yourself, you know, so you become self-aware. And essentially you were saying most people are not aware of what drive them, or, you know, why they ended up doing what they’re doing. They don’t ask themselves the questions.

So you serve a very important function, which is anchoring people to their experience. How much does that reflect on you building what’s become a tremendously successful business? But it’s doing something that seems to me to have its roots back in your childhood.

Dan Sullivan: Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. I would say that who I was at 6 I’m closest to today at 78.

Jeff Madoff: How would you encapsulate that description?

Dan Sullivan: Well, just very keenly, keenly interested in how other people think about their experiences. And then I think a skill I’ve done, that I’ve added to it, is because I’m doing it with a lot of people I can distill certain principles that everybody’s experiences relate to, and then I can feed those principles back to them and actually depersonalize them, you know?

For example, there’s something that I’ve noticed that a lot of people who are not entrepreneurs—and in the broadest sense of the word ’entrepreneur’, or someone who’s willing to hit the marketplace straight-on with just their talent and their ambition. That’s how I would describe… In other words, they’re not looking for an intermediary buffer that will guarantee them an income if they fail. OK? So they’re taking an ownership over their forward motion that most people don’t. They just don’t. They expect there to be an employer who provides the buffer and the guarantee and the structure and the process so that they can develop themselves, and for some reason entrepreneurs just decide to do this, take total ownership of the entire project.

But one of the things that I often notice when I’m talking to young people who are in their teens—’cause I meet a lot of them through the children of my team members, or people not too far out of their teens who are actually employees at Strategic Coach, or they’re the children of our entrepreneurs—and they have a condition to going out into the marketplace and that is that they’ll have the confidence to do it, that they’ll have the confidence to actually go out into the marketplace.

And I said, “If you’re looking for confidence to go out into the marketplace, you’re going to wait forever.”

And they said, “Well, what I mean by confidence is that I have the capability.”

I said, “Ohh, that’s even tougher. That’s even tougher. So you what you’re saying, ’I want to know already what I’m gonna learn when I go out into the marketplace.’” And I said, “You’ve just put in front of you two obstacles that are going to keep you from… You’re demanding up-front the confidence and the capability that can only come from actually being out there, but you won’t go out there until you have these two things.”

So they created two conditions. And I said, “I tell you what entrepreneurs do: They make a commitment that they’re gonna be out there and be successful before they have the capability and confidence to do it.”

Jeff Madoff: So what is the difference between confidence and courage?

Dan Sullivan: Confidence feels good. Courage doesn’t feel good.

Jeff Madoff: Because you know you’re taking a chance.

Dan Sullivan: Well, you could fail. You know, as a matter of fact, the odds of you failing are quite a bit higher than succeeding because you don’t have the capability yet.

So you have the commitment that you’re going to do it, which puts you into a period of courage when the only thing getting you out of bed in the morning and going through the day is that you made the commitment and you have the courage to keep going with the belief that if you’re out there long enough, the capability is going to come.

And in fact I think that’s what creates the capability. It’s a catalytic combination of commitment and courage that actually creates capability. Your director, I’m eager to get his book. Sheldon.

Jeff Madoff: Sheldon Epps.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I’m really interested in getting his book, because I think without reading the book, what will be reflected in his book is exactly the process I said: There was a commitment and there was courage.

Jeff Madoff: You’re right. There was the courage, because everything— and one of the most striking parts to me in Sheldon’s book was he was always referred to as either “the first” or “the only” in being a Black director. And then becoming the leader and establishing the national reputational capacity in The Playhouse, and then on the Broadway and the West End and all of that.

So, two questions I have: You talk about capability. You talk about courage. How would you define capability? What does that actually mean?

Dan Sullivan: Well, capability is that you’ve clearly identified the actions. There’s a set of decisions, communications, and actions that actually get a tangible result, which shows up in you getting paid. Until you get the first paycheck, you don’t know what that is. And then you get the first paycheck, and you say, “Now, how did I do that again?” You know?

And my sense is that after you get the first check, about 50% of what’s needed for the next one is now a a sure thing. And even when there’s failure, which there will be continually. There will be a continual process that consists of success and failure. It’s trial and it’s error, and then it’s learning, and then you begin to realize it’s not 10 things, it’s two or three things properly put together that actually represents the capability. OK? Yeah. That’s a universe of three things, in other words.

But the first thing I’ve known, and it’s a rule of mine, is that I never tried to sell anyone on something that I’m not 100% already sold on. OK? Because my being 100% confident in myself is actually part of what they’re buying.

Jeff Madoff: Absolutely. Yeah. I think that’s true. I know one of the ways you put it is there’s two sales and the first sale is to yourself.

Dan Sullivan: And don’t be talking about the second sale at all until the first sale is actually made…

Jeff Madoff: Oh, absolutely.

Dan Sullivan: …because you’re asking another person to take a risk, too.

Jeff Madoff: That’s right. That’s right.

Dan Sullivan: Don’t ask someone to take a risk on someone who’s not sure himself.

Jeff Madoff: You engage entrepreneurs and they engage and join Strategic Coach. Part of what you do to them, what they’re getting value from, is the questions and the tools to unearth the answers for those questions in the hopes of creating a more successful business. Yeah, right?

So that takes me into two areas that I want to explore a bit.

Dan Sullivan: Well, let me go back and ask a question. If I take the play Personality from its inception when you did the documentary on Lloyd Price and you saw the script that you wrote that ended up as being the dialog of the documentary. Your long experience of putting together other productions where they have to have a message, they have to have a deliverable as far as some new meaning as being created here, and you spotted something and said, “He’s got everything here. He, you know, he’s got the history, he’s got the track record, he’s got the celebrity, he’s got the awards, he’s got the time period, he’s got the music. He’s got everything that could make into a Broadway musical.”

I’m seeing what was going on in Jeff Madoff’s head here, and at a certain point, you’re going to make a commitment to Lloyd that “I’m going to work with you to try to turn this into something that, right now, the two of us know it, maybe a few other people, but there’s going to be a point in the future where thousands, tens of thousands of people are going to know this story. And it’s your story. But I’m going to put it in such a way that it can attract top talent. It can attract investment.”

And I’m saying that probably for the first year and a half, two years, three years of that process, you were operating almost entirely in the realm of commitment and courage.

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, there wasn’t much else, so probably there was. There was everything else.

Dan Sullivan: But you’ve done this enough in your lifetime with other types of projects, starting with the fashion industry, starting with the plays in your basement when you were in Akron, Ohio and everything, you’ve gone through this “Deliver a presentation, and if it’s interesting enough, they’ll come. And if it’s really interesting, they’ll come back a second time.” And you’ve translated this into the fashion industry. You’ve translated this into the season debut industry with top-notch fashion brands and you’ve done this enough that there’s a real capability here where worrying about how you’re gonna do is no longer part of the question. It’s not the challenge, you know? “Well, am I up to it?” There’s a point where you cross over. “Well, I’m committed, so I’m up to it.”

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, I think that’s being a professional. You know? Yeah, I think you just defined what being a professional is: It’s not taking something on the deciding you’re not interested. You know, you take it on and then you deliver the goods. And if you’re interest wanes during the process, you need to put that aside because you have made a professional commitment to deliver. And so you deliver.

Dan Sullivan: Something here I’d like to relate to your teaching at The New School, just the brief glimpses that I’ve got it from actually being in the presentation hall, and you interviewing Kathy Ireland that particular day. And then I saw another one where you talked about brands and you went through brands.

And those students who were sitting there, and what would you say the age range is? But it seems to me that they haven’t bet on their future. A lot of them just haven’t bet on their future. They’ve guessed about their future in the sense that it’s brought them to you and your class. They’ve guessed, but they haven’t actually bet on their guess yet.

Jeff Madoff: I think that’s true in most of the cases. And it’s interesting because there are students who were on the older end, like 26, 27 who maybe went into military service. Or just did something else and then made the decision to come back to school. Those students, inevitably have a higher commitment because they’re going back because they want to, and I think a lot of people go on to college just because that’s what their parents want and that’s what they think they ought to be doing, is you finish high school and you go to college.

When we were growing up, there was no such thing as a gap year. You know, you just went on to college. If you could get in.

So you’re right, they’re still in that exploratory phase, but they might not even know that they’re really exploring. There hasn’t been, of all the different points of light there hasn’t been a constellation yet formed in their mind that drives them towards a goal. So you’re correct.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, my sense it’s a fork in the road. It’s a Yogi Berra moment.

Jeff Madoff: “When you get to the fork-“

Dan Sullivan: “When you come to the fork in the road, take it.”

Jeff Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but my sense is out of 20—I’m just thinking here, I’m looking at the statistics—of 20 people who are in your class, who probably over the next 20 years are going to get into something related, kind of, to the direction that they’re already going in. But they won’t be entrepreneurs. Only one of them will actually be an entrepreneur. And the reason is they’re looking for evidence that they’re they’re making the right decision from things outside of themselves, not from something inside of themselves.

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, I think that’s probably true, although I do think there are those that are just oriented towards wanting to start their own business, and they may not even quite know what that business is, but that’s the direction they want to go.

And then there are others who may not want to start their own business but have an ambition to be significant and have a significant impact in some much larger business, and that happens.

There was a student that I had who often had excuses for his work not being finished. It was clear from his contribution in class that he was very, very bright. So the third time that I got a lousy excuse for the work not being done, I asked him stay after class and I said to him, “Look, you’re very bright. And I’m sure you have gotten by up to this point at doing the minimum. And you’ve got to ask yourself, is doing the minimum so you can get by how you want to live your life? Because you can do that. You’re smart enough to coast. But I don’t think you’ll find satisfaction. I don’t think you’ll find fulfillment. And ultimately, I don’t think you’ll find success, because you haven’t found satisfaction or found fulfillment. So, you know, it’s up to you whether you get an A or a C in class. To me, I think it’s just unfortunate because I think that you’ve got talent that you could be honing. But that’s up to you. And then you need to make your decision. But do me a favor. I’m smart enough to know that your excuses are bullshit. So just say ’I didn’t do it.’ I don’t want to hear a narrative around it, because you’re already repeating the narrative by the third time. It’s the same excuse. I don’t need to hear that. I know the punchline.”

Anyhow, it was really cool: He ended up did do more. But he also ended up getting a very good job in which he has ascended, and I had him come back and talk to the class. I put together “Life After Parsons”, a panel, and I would have three former students who are out of school anywhere from three to five years. “How was it actually getting a job?” You know, all of these things that the students are really curious about and he had mentioned, you know, what I said to him. That was kind of the turning point for him, which it touched me, because I was hoping that it would wake him up.

Because the one thing as we get older we realize is that, you know, money may come and go. The time only goes. I think when you’re young, you have that perception of an infinite supply of time, it goes fast. And so I was glad that I had that kind of effect on him. Didn’t know that I would, but I also felt like he was smart enough to get it if I came at it in a way that wasn’t putting him on the defensive or attacking him or telling him “Oh, you’re not living up to your potential,” or any of that kind of thing.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the other thing is that he was taking advantage of something that I’ll call, that didn’t really exist when I was, nor for you in the 1950s and 1960s, and that was social promotion, and that there’s such a what I would say sensitivity to a concept that I would call self-esteem, that you don’t want to say anything or be the source of any kind of negative feedback that will be the straw that breaks somebody’s sense of self esteem, and then you’ll be responsible somewhat for their subsequent failure because you gave them a hard lesson.

I’ve never believed in self-esteem. I believe in self-confidence that comes from actually doing something and having proof from the outside world that you’ve done something that other people find valuable. That’s not self-esteem, that’s self-confidence.

Jeff Madoff: I agree with you, although having taught so many students at this point and just being an observer of human behavior, there are certainly people that have just had the crap beaten out of them by parents or teachers, or whatever, at a very young age. They don’t have the self-esteem because they’ve been constantly told they’re not good enough, they’re not smart enough, and there has been a criteria that that other person talking to them wanted this person to fulfill.

And I’m not saying like what we’re talking about before doing a professional job. I’m just saying that they spent a lot of time without any sense of compassion or empathy or anything, and so it was very hard to generate the belief in themselves until somebody actually cared enough to help them.

And it’s interesting, by the way, is it’s not just that somebody else cared enough. It’s so many times people don’t even believe they can, and it’s surprising—and I’ve met very financially, very successful people who still don’t have self-confidence.

Dan Sullivan: Me, too.

Jeff Madoff: And you would think with, you know, considering who your clients are, all entrepreneurs, and you know, they’ve got to be at a certain level just to afford your services. Yet on the outside they have that criteria that they have their own business, they’ve generated the revenue to be able to avail themselves of your services of the lifestyle that they have, but they still don’t have the self-confidence. Who are often, by the way, I find most difficult people to work for.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. Well, it’s interesting, because I know it when I see it. I know self-confidence when I encounter it. OK? One is that they’re not very self-referential.

Jeff Madoff: And what do you mean by that?

Dan Sullivan: Well, they’re kind of handled as far as they’re concerned. They’re sort of handled. They know how the game works and they know how the next jump that they’re going to take, how it’s going to be. And they know that they’re going to have fear. They know that there’s going to be excitement, and it’s the thirtieth time, fortieth, hundredth time that they’ve done it, so they experience fear totally differently, that people who are self-confident experience fear totally differently than people who have self-esteem but not confidence. And what I mean by that, that there’s sort of a social status that’s related to self-esteem, where I think self-confidence is strictly an individual, alone path, and you don’t expect others to be giving you the support and the reinforcement to go forward.

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, I think that’s true. But I think that also foundationally that happens pretty young.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. The other thing is that you may just have been born with it.

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, I came by being an entrepreneur honestly. My mom and dad were entrepreneurs. My sister is an entrepreneur. And that to me just, you know, I never thought, “Oh, I’d love to go up and get a job.” So that was just wasn’t part of the equation, you know? I knew that I would be starting my own business. I didn’t know what it was. And the first business I started happened by accident. You know, it was complete serendipity. But I did have the confidence that if I applied myself I could make it happen. I could make it work.

I was never intimidated by a task that I chose to take on. Which did not mean that I didn’t have any fear or it didn’t mean that I wasn’t aware of risk.

Dan Sullivan: Oh yeah.

Jeff Madoff: But that wasn’t going to stop me. You know, the play is daunting at every step. And it takes, you know, so much to get it going. And I mean, in your case, how long? Not only has Strategic Coach survived, but thrived, even through some of the most difficult times, like what we’ve been through in the last few years.

So you know you’ve got the confidence, which is well rooted in experience that you can do that. But how many businesses do you see or the individual entrepreneurs, I should say, that screw it up along the way? And what would you say is the primary thing once somebody’s got an ongoing business that’s doing reasonably well, is there any unity in terms of what that tripping-point is that screws them up?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, there’s a question that I asked them. This is all the entrepreneurs. I said, “You’ve had long entrepreneurial experience.”

So mine started in 1974, OK? So it’s 49 years this year. But if people ask me about the company, the company I have today, they say, “When does the company actually start?”

And I said, “1989.” So there’s 15 years between 74 and 89, which I call “The R&D Period”, OK?

Now I wasn’t employed at any time. During those 15 years, OK? But I was scrambling for any kind of job. Project, a project job that I could complete for somebody and get paid in an entrepreneurial fashion.

So when I asked them the question, “In your mind, when does the company you have today actually start? When you can see a clear, you know?”

It’s like royalty: When does the royal line? Actually starting and I know there’s a lot of bastards back there and you know you know mistakes and everything else, and none of them have the actual time when they decided to go out into the marketplace and just live as an entrepreneur. None of them have that date as the starting point. It’s further along the line when they have a system, when they have a team, when they have a business cycle.

Yeah, there’s a pregnancy period, but you know. Definitely when they get slapped and they cry, that’s when the business starts.

Jeff Madoff: So there are other questions that I think are really important to go along with this. One of those questions is “What is success?” What does that look like to you? Because you and I both know lots of people who financially have more money than they could ever spend. There’s nothing they need to say no to in terms of they want to buy.

Dan Sullivan: “More money than meaning,” I call it.

Jeff Madoff: Well, that’s a better way of putting it. You’re right. “More money than meaning.” I like that. That’s good.

So what are the questions that you ask people? Or how do you define what success is for you in business?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. So I always go back to the “fear and excitement” factor. And I say, “What’s the next project that you can envision right now that—two things: You don’t have the capability yet to pull it off, and you don’t have the confidence that it’s going to be a success. But it intrigues you so much that you find that if you pull it off, it’s gonna be the most exciting thing you’ve ever done. And it scares you because you’ve failed before and you can fail with this one. You’ve had this feeling before where there was something exciting, you took it on and you didn’t pull it off. So what would be the thing that checks all the boxes here of what I laid it up?”

And it’s really big, it’s really big. It’s the biggest thing I’ve ever done and it requires personal change on their part of just doing the part that they’re great at and then depending on other people’s great skills to do the other part.

I would say that if you can ask them that question, and they respond and then it becomes a plan they’re going to jump to the next level and then they’re going to have a situation where they have more meaning than money.

(laughs)

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, well.

Dan Sullivan: And then the money catches up.

Jeff Madoff: Yeah. And what you’re talking about, that process, is certainly a process I’ve been going through.

Dan Sullivan: You know, yeah, you’re just another one of my adults. You know, I’m just. (Laughs)

No, but I have a lot of them now. I have a lot of adults who are just—some of them in their twenties, a lot of them in their sixties who are now—it’s the biggest thing they’ve ever done, and it scares them.

But the big thing is they’ve learned not to do it alone.

Jeff Madoff: That’s right. No, that’s huge. That’s huge.

And I think when you’re young, and I know part of, with me, when I started my first business is, “Well, how do you pay for those people?” And when it’s been so hard to start even taking out a regular paycheck yourself.

And I think that one of the big problems I’ve seen with so many entrepreneurs is they don’t know how to delegate, and that they end up trapping themselves, because then “Well, by the time I explain to somebody I might as well do it myself.” And that’s not a sustainable way to be if you want to grow a business. Or have a life, you know?

And certainly, you know, with my fashion company, it was all funded through revenue. Same thing with my production company. When I embarked on the play, there was no way to build it through revenue because there was nothing to create revenue with until I got it all together, and putting together the best possible team to execute on that promise of what this could be, you know?, that became another whole huge activity, is finding and enlisting the right talents to help realize the vision of. And so putting together that team was critical, otherwise it just wouldn’t happen. You can’t do it.

Dan Sullivan: I’ve noticed a fair amount of good fortune that’s accompanied your play that, had it been done five years earlier or five years later, wouldn’t have been there. And I can list two or three of them. I think I’ve mentioned them in passing before that, but you caught America right at the time when it needs a happy racial story. And there aren’t any out there. There aren’t any out there. OK?

And the Black/white thing has been, you know, a subject of constant turmoil from day one in the country. OK? Because on the one hand, to the degree that the US is a civic religion, the religious papers, the Declaration and the Constitution says it’s a country where everybody gets an equal opportunity to succeed. But when you dig down to the individual level, it’s never true. Not down to the group level, but to the individual level, you know? And you could find 20 people for whom that wasn’t true.

But if I look at your own play, it’s the guy from Hollywood, the record producer, who is trying to take a big jump himself I mean, he was guessing and betting on his own career, because he wasn’t a known person at that time, but he had a nose that there was a change in the air, you know, in terms of where music was going, where recorded music was going, how recorded music would be listened to, and who would be buying the records and who would be showing up for the concerts that he met this 17 then?

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, that’s right.

Dan Sullivan: Seventeen-year-old, and he said, “This kind of checks all the boxes of what I’m looking for.”

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, you’re talking about Art Rupe, who just died, last year?

Dan Sullivan: Who just died.

Jeff Madoff: A hundred and four years old. That’s right.

You know, it was funny, by the way, just a quick sidebar is when Art was turning 100. Yeah, I said to Lloyd, “You know, I saw it’s Art Rupe’s birthday coming. He’s going to be 100.”

He goes, “Yeah, I know. I was thinking of calling him. I haven’t talked to him for a few years. You think I ought to call him?”

I said, “Lloyd, he’s 100. I don’t know how many chances you’ll have. Yeah. Call him. I would. “And he did. And he had a great conversation with him, just oddly, although Lloyd was 14 years younger than him, or 15 years younger, Lloyd died first. But that was a couple of years after that and he did speak to Art, wished him a happy birthday, and they talked for a while. I thought that was just really, really cool.

Dan Sullivan: Now many 100-year-olds get a visit from an 83-year-old experience.

Jeff Madoff: Yeah. No, it’s it’s pretty amazing. It is pretty amazing.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, no, I mean and that’s part of the luck of the play that you put together. Those are like bookends to 80-year period of history.

And the other thing is that you presented your idea for the first time right up when I think there was a revolution going on culturally and socially where the most talented people had the worst history to deal with, and I was struck when I was at the workshop, and I said, “You know, you can’t put this play together anywhere that within 3 miles of where we’re sitting, you got all the talent in the world to do anything you want with this play.” And that was in ‘19, I think that was in the April of ‘19 and the next year you had even more all the talent in the world. OK?

But the other thing was that the biggest test that the play was going to go forward had nothing to do with the play. It had to do with what was going on socially, politically, and economically in the whole world, but especially in the country. And the people who chose to be with you stayed with you.

Jeff Madoff: That’s right.

Dan Sullivan: And that’s another piece of good fortune.

Jeff Madoff: That’s right.

So you know, in terms of that, going back to the notion of, “So what is success?”

Dan Sullivan: Well meaning to, I’m being the official historian here at the whole process.

Jeff Madoff: You know success, to me is, you know, it’s a combination of things, but it’s also those people who help you get there. Number one, honoring that, because you know whatever I wrote, and I’m proud of what I’ve written, but you know, without the supporting talents, it doesn’t go anywhere. You know, it’s not like you write a book—and that’s a whole other story—but you know, it takes the talents to get out there and those who choose to stay with you, I haven’t had anybody drop out. And I think that’s unusual.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And I think that’s noticed. I think that’s noticed, you know, and you’re hitting Chicago right at comeback time for, I mean, Chicago has real challenges ahead of it as the city. The population’s down since 2010. The city’s population is down. You know there’s lots of reasons for it. But you’re catching that city right at the time when they need a knockout play. They just need a brand-new, original, top of the class, breakthrough theatrical production, and you’ve got a, I don’t know, it’s an 80-, 90-year-old theater?

Jeff Madoff: Actually, this is their 100th birthday. The theater opened in 2023.

Dan Sullivan: 1923.

Jeff Madoff: I mean 1923, yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. What does centuries mean after a while?

Jeff Madoff: That’s right. You know, when you get to be our age, what’s another century? It’s a rounding error.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And it’s funny that the name of the theater should be Studebaker because, as my memory of American cars goes, is that the early 1950s were kind of the end of the Studebaker run, you know, like-

Jeff Madoff: Well, what was interesting is the building that we’re in, the Design Arts Building, was the Studebaker Carriage Company before there were even cars. That opened in 1890. The theater opened in 23 and 1923, but it iterated and became The Studebaker Motor Company.

I’m not exactly sure of these numbers. I think it’s the fourth generation now. The real estate company that owns the design Arts building, which is a 10-story building, the theater’s on the main floor. The other nine floors are rehearsal rooms, voice teachers, acting teachers, musical instrument makers, bookstores, all this stuff, and the building’s mission from the beginning was to support the arts. And so this day, and now the woman is running it, who I think it’s 4th generation, she’s in her thirties. She has stuck to that same mission. And when I sent you the update. I hope you’ll have the time, because you’ll love it to just go floor to floor just to look at what this place is because it’s very cool. It’s very cool, but-

Dan Sullivan: No, I’m just saying that there’s something epic, you know, and I read enough history to know that these are not predictable. You can’t create them with intention. But a lot of things fall in place around certain—and I think cultural events is a prime one where, like, just the right people at the right time, get together at the right place and they produce the right result and it becomes really big. And I think that you’re fortunate.

And you made it up.

Jeff Madoff: Well, you know, it’s funny when you said the difference for the check-boxes you said. The only check-box I had was “Wow, this is a really great story that’s never been told.” And I didn’t-

Dan Sullivan: It shows. It shows.

Jeff Madoff: I didn’t go through, “So what’s the financial viability of this?”

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. “Where is this going to put me?”, you know.

Jeff Madoff: No, it’s just “This is a story that needs to be told, and people don’t know this.”

And now, having sat with audiences, you know, initially I was watching the play. Then I just started watching the audience and what they were responding to, and that was so interesting.

It’s cause stuff that people didn’t know and when they heard it, whether it was, you know, the Lloyd counseling Sam Cooke on, you know, “Take the Jesus out,” and that became “You Send Me.” Instead of “Jesus, You Send Me.”

And then the audience, there’s this audible “Ahh,” and they get it. And, you know, that’s just kind of, I think it’s important, but it’s also fun knowledge. You know, it’s cool.

But what I wanted to get to—of course I’m happy talking about my play, right?

Dan Sullivan: No, no, no. And we’re talking about entrepreneurism here and, you know, the original definition of “entrepreneurism” as we have it, it only goes back to 1804, and it’s a Frenchman, an economist. And there weren’t economists in those days. They didn’t call them “economists”, but he was a big fan of Adam Smith.

So Adam Smith created The Wealth of Nations that came out in June, I think, of 1776, OK? And it’s basically his observation as a professor of moral philosophy in Edinburgh. He was just noticing that a new economic factor had been created, which the present state of government in the UK, which the present state of understanding of economics, wasn’t taking account for, but that there was now great breakthroughs that are possible.

And you have to understand that the Industrial Revolution as we properly understood it started three months before he wrote this book. So he had been writing this book probably for 10 years or so.

But in the March of 1776, James Watt, a fellow Scot, created the first steam engine, where you got a +25% energy output. In other words, whatever you put into it, you got 25% more. And that’s actually the crossover. That’s the crossover, it’s the first time you have a man-made technology that produces energy.

So the Declaration of Independence was a month after Adam Smith wrote the book, and the book was very popular, and it was most popular in the US colonies, who were all British, you know, they were all British citizens, wanted to be considered British citizens.

But he essentially created a new economic concept, which was The Innovation Theory of Value. OK, that the wealth is not in the raw materials, the wealth is not in the labor. The wealth is in the putting-together of large numbers of humans in teams to produce an innovative breakthrough. And he said, “That’s where the value of economics is.”

And this contrasts to Marx, who’s 50 years later, 70 years later, who said The Labor Theory of Value: There’s no value except the labor. And that was the wrong-headed one-way street coming off this. And the reason is that they couldn’t understand how just putting these things together could create new value that had never existed before. You know, it was a fundamental breakthrough, and I think that was an epic moment.

Jeff Madoff: That’s why it’s magic. That’s right.

Dan Sullivan: It’s hard to wrap your mind around magic, but it is possible to know that you’re in a magical experience. And mostly it’s what you don’t do that’s most important.

Jeff Madoff: Explain that.

Dan Sullivan: Well, like I think Strategic Coach, I think a lot of our existence is quite magical, that I’ve hit on something that if you get entrepreneurs actually collaborating with each other you can escape from the restrictions of competition. I think it’s a magical thought. OK? And not everybody gets it. But the ones who do, they start producing amazing results.

So you know, I feel at 78 I’m, you know, in the most magical period of my life. And as I observe you, I think you’re in the most magical part of your life. And you should have been retired a long time ago.

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, the problem is I don’t golf. I don’t fish. I don’t play cards. So you know, by default…

Dan Sullivan: And you got more meaning than you have money. Yeah. And we both have a lot of meaning. But we have enough money to make that a central project.

Jeff Madoff: Well, so let me ask something about that meaning and money.

I believe that you know an awful lot of people who have plenty of money. They’ve been successful in their business, but somehow hit a point of “Is that all there is?” And even depression, because, you know, their goals were to make money. They’ve made money. Their goals were, you know, “If I had more time I’d do X.” And they can’t afford to take more time.

Why is it that so many people, do you think, hit that point where, despite what on the outside looks like very successful business, they’re somehow unhappy or unfulfilled.

Dan Sullivan: I’ve been writing about this lately that they didn’t realize that it was a game that they’ve been involved in all their life, and the central purpose of the game is growth. And they thought the purpose of the game was status.

Jeff Madoff: Now, growth in what way?

Dan Sullivan: That you do one level of growth, and then you’re presented with the fact that you have to go back and start over again and do a new level of growth. And so you go from being totally accomplished to starting all over again at another level.

Jeff Madoff: But do you think that’s-?

Dan Sullivan: What I’m saying there’s great meaning in that.

Jeff Madoff: In that other level.

Dan Sullivan: No matter what level of accomplishment and achievement and reward you get to, that’s just the chips that you put on the table for the for the next deal, OK? You’re going to a higher level.

Jeff Madoff: But why do you think that is that there are so many people that get into their forties or fifties or sixties and they just feel they’re not happy, even though they have what appears to be all the trappings of success. They somehow are not happy.

Do they even ever define what happiness is? That’s the question I guess.

Dan Sullivan: No, no. You have to look at it at a individual case, you know, and everything else. But I was watching one of the great tech—and I I won’t name names here, but one of the great, you know, historic titans of technology is in his seventies, no early seventies, late sixties. He’s talking about all the philanthropic work that he’s doing, and for some reason, at a certain point they all want to save the world, where just making payroll was more interesting.

You know, they’re doing this, and they’re doing this, and they’re taking jet flights here, and they’re taking jet flights here, and they’re being invited to this gala, and this everything. And I said, “You know, I really feel sorry for you because you can’t experience that fear and excitement that you had when you were nineteen. You’re way, way past when you could ever experience the fear and excitement that you had when you were 19 and you were working out of a garage or you were working out of a warehouse and you knew you had something, but the world didn’t see it yet and you had to get bailed out by friends. You had to get bailed out by family. You had to get bailed out by 25 different credit card companies and everything.”

And I said, “You’d do anything to have that sense of excitement and fear again, but you can’t buy it.”

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, it’s really fascinating to me, you know?

Dan Sullivan: Why is Clint Eastwood in his nineties still taking risks with his reputation?

Jeff Madoff: Well, I agree with you. Same thing at 100, you can say for Norman Lear, you know, he’s still producing new programs, and…

Yeah, my whole thing is when I talk to people now, there’s something they really want to do. And they haven’t done it yet, and I say, “Well. I’ll tell you the question I asked myself, if that’s any help to you, which is ‘Well, if not now, when? What are you waiting for?’” You know?

Dan Sullivan: Well, “And what’s everything I’ve done mean if I stop now? I never stopped before. Why am I stopping now?”

You know? I mean, that’s the way I look at it. I had no reason to stop before. Why do I have a reason to stop now?

Jeff Madoff: Enjoying the fruits of your labor, Dan. Sitting back and just counting the coins, you know?

Dan Sullivan: No, I mean this is, we’re right at the center of entrepreneurism right here, I mean, what we’re talking about here, you know, and it’s about growth. It’s about growth. You can literally, by putting the right elements together, the right factors together, you can create something that’s never existed before.

Jeff Madoff: I would add to that maybe it’s already embodied in in your meaning of it, too.

To me, the growth is also creative growth, emotional growth, the growth of relationships, those kinds of things that aren’t the same tangible thing as growth of your bank account.

Dan Sullivan: And the growth of meaning, yeah. That’s what we are: We’re meaning-makers, you know.

Jeff Madoff: So then, what do you think then is the meaning of happiness, and can you be successful without being happy?

Dan Sullivan: I think it’s in the movement. I think it’s in the moment you have to be moving to be happy. I think happiness is an activity, OK? And one of the things that makes it happy is the fact that you know you’ve gotten better at it all along by who you’re attracting into your life.

Jeff Madoff: That’s interesting, and go a little deeper into that.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the cast, the permanent team that you put together with this. You can’t buy them. You bought them with meaning, and the meaning exists before you talk to the first one.

Jeff Madoff: Well, you know, interestingly, I think that in terms of at least, so far, in the necessary fund-raising I’ve been doing for the play, I haven’t had to sell anybody. And talk about what I’m doing-

Dan Sullivan: You’re the buyer.

Jeff Madoff: That’s right. That’s right. And that you have the chance to have that same kind of experience if you’re involved. You know, because quite the contrary. I’m not saying to people, you know…

I was asked by someone who’s become a very major investor, “Is this a good investment?”, before he put in any money at all?

I said, “How do you mean good investment? Do you mean is it going to guarantee that you are going to profit from this investment? No, it’s not a good investment if you’re looking for that, you know, invest in bonds or-“

Dan Sullivan: CDs.

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, CDs. “But you’re not getting a high multiple, which you might get with this. But the one thing I can say to you is if you participate it’s going to be a fascinating ride. But I’m not going to try to convince you to invest in it. You know, it’s either going to be there on the table and you recognize what it is and you want to be a part of that, or it’s too chancy a thing for you. And if that’s the case, because whatever you put in, you should be prepared to lose, you know? So with that in mind, you know, I think it’s a hell of a lot more fun and much more of a fulfilling journey than investing in an app, you know? But that app may make you a lot more money.” Who knows?

And by the way, I don’t think the failure rate in theater is any higher than business in general.

Dan Sullivan: Certainly not higher than the technology world that I’ve had some insight into over the last 10 years. The only people that I think that have sort of screwed up the technology world were not the people who were betting on the product, they were betting on the bet.

Jeff Madoff: And that distinction being-?

Dan Sullivan: Well, that’s what they do in Las Vegas: The house always gets its 17%, whether the people who are gambling are happy or not.

Jeff Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And I think that there is a point where it became about the early offerings of a new possibility. There was enormous amounts of money, and a lot of people would get a payout from being the first money in. Because they would get rewarded. You know, there’s a guy named Ponzi…

Jeff Madoff: Out of Boston, yes. He had a scheme, I believe.

Dan Sullivan: Charles, I think, the proper name. Charles.

What I’ve noticed is that there’s a lot more hype in the technology world than there was is when I first started getting interested in the 1970s with the microchip. You know, the microchip was opening the door to something new.

But people were really committed to new products, things that would actually change how work got done. And I don’t think that that type of intention has been for a long time.

And the trial, which is coming up because he’s pleading not guilty, of the FDX guy, Sam-

Jeff Madoff: Bankman-Fried, or something? Yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, there’s an actual video of him presenting to Sequoia, which is a big venture capital firm, and he got out of the meeting when he was actually playing a game. He was gaming while he was on the call with the venture partners at Sequoia, and this will be evidence, so I’m not talking about anything… And they’ve taken down the video, but it’s hard to take down the video. Everybody’s got the-

Jeff Madoff: Yeah, that’s right.

Dan Sullivan: Video you know. Even Jeffrey Epstein stuff out there that, you think it’s gone? It’s not gone. Somebody’s got it.

But anyway, they’re betting $210 million on a guy who’s literally done nothing, and the guy says, “I just love the founder. He’s such a great founder,” you know? And everything like that. And what they were seeing is that they could create a rush that would just inflate the price of the stock and they’d all get their money back from the inflation of the stock offering. You could just see them. There wasn’t anything that he was creating something valuable, which he, it turns out, really wasn’t.

Jeff Madoff: That’s an understatement at this point, yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, Warren Buffett said, “Now,” he said, “a Nebraska corn field, now that has value. First of all, the land has value. The crop has value”. He says, “This stuff,” he says, “I just think it’s going to come to a bad ending, you know?” He said, “Something happened with the Dutch with tulips about this, long time ago.”

But the thing is that I think a lot of people, when they no longer have the thrill of creating something new, it’s the thrill of making a killing that keeps them going. But in the end, what do you do with a killing?

Jeff Madoff: You have to bury it.

Dan Sullivan: And who remembers the killing, you know? A month later, who remembers that? You know, after you’ve got 15,000 square feet of house, does another house do you any good?

So I think the thing is that there’s a lot of money. The other thing you’re fortunate about, there’s just a lot of money out there looking for a purpose. But the value that you’ve created over the last five years is incontestable. Where you are right now with it is as solid as any of the Gershwin stuff.

Jeff Madoff: As my grandmother used to say, “From your mouth to God’s ears,” although she had a heavy Czech accent, and it always sounded like “From your mouth to Godzilla.”

Dan Sullivan: But you have an advantage: You’re still alive, they’re not. Yeah, but no. I think there’s going to be a real renaissance of this historical period.

So anyway, those are just someone from outside the process who’s just observing it.

But I think the big thing is that the happiness is in the creation. The happiness is in the movement.

Jeff Madoff: The process.

Dan Sullivan: The happiness is in the risking. The happiness is in the fear. The happiness is in the excitement. The happiness is in the teamwork.

Jeff Madoff: That’s right, because from that-

Dan Sullivan: That’s where the value gets created.

Jeff Madoff: And that the stories get created, because, you know, that will create new stories, you know?

To your point about magical thinking, is I think that when those people are looking to make a killing, which almost never works out, the thing I’ve always wondered when I hear about “making a killing” when I think of killing it means somebody dies. And isn’t it wonderful if everybody lives and is standing and applauding and smiling? That’s, to me, happiness, and realizing that happiness is also transitory but fulfillment is something that can, I think, propel you forward through life and relationships, because the meaning you are speaking about is ultimately, I think…

Once you’ve got the basics covered and you can feed your family and provide shelter, the meaning, I think is what’s so critical. And I never want to go into business with people who want to make a killing. Those aren’t the kind of people I want to be involved with. Obviously, I hope we do really well and make a lot of money. But no one is harmed in the process.

Dan Sullivan: Well, you just want it to take on new life. You know, there’s a next growth stage after the one that you’re currently in. So I remember I had the two authors of Chicken Soup for the Soul in the Program for probably three years each, and their big thing was that they were now on version 55, you know, “The Lutheran Chicken for the Soul,” you know. They had to come up with new names, and they weren’t even writing that. Other people were writing it and they were just taking the royalties, and one of them you could actually have a philosophical discussion with. And I said, “You’re in your fifties and you’ve made it big beyond your wildest expectations and you’re feeling totally trapped.”

He said, “That’s right.” He said, “This is all I’ll be remembered for.”

And I said, “Yep, got to get out there and create some new meaning.”

Jeff Madoff: Well, that’s a great way of putting it and I think that that’s a great, not only ending to our conversation—“Get out there and create some meaning.”

Dan Sullivan: You always have to be in the business of creating new meaning. You can never retire from that.

Jeff Madoff: Well, this has been another wonderful conversation with my friend.

Dan Sullivan: Funded. I thought it was funded actually.

Jeff Madoff: That’s an artificial sweetener, isn’t it? Oh, that’s Splenda. I’m sorry.

It’s been wonderful. And so once again, having a delightful time, which we hope that you all enjoy listening to, with my friend Dan Sullivan and “Anything and Everything.”

And please, you know, leave a review. And spread the word, ‘cause good ideas.

Dan Sullivan: We’re going to attach it here, but the actual latest update on the musical Personality. This will be included, so that they can just go and click and actually do the-

Jeff Madoff: Oh cool. Well, thank you.

Dan Sullivan: And make their plans for Chicago.

Jeff Madoff: Terrific.

All right, Dan, thank you very much.

Dan Sullivan: Thank you, Jeff.

Jeff Madoff: Thanks for joining us today on our show, “Anything and Everything”. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend.

For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

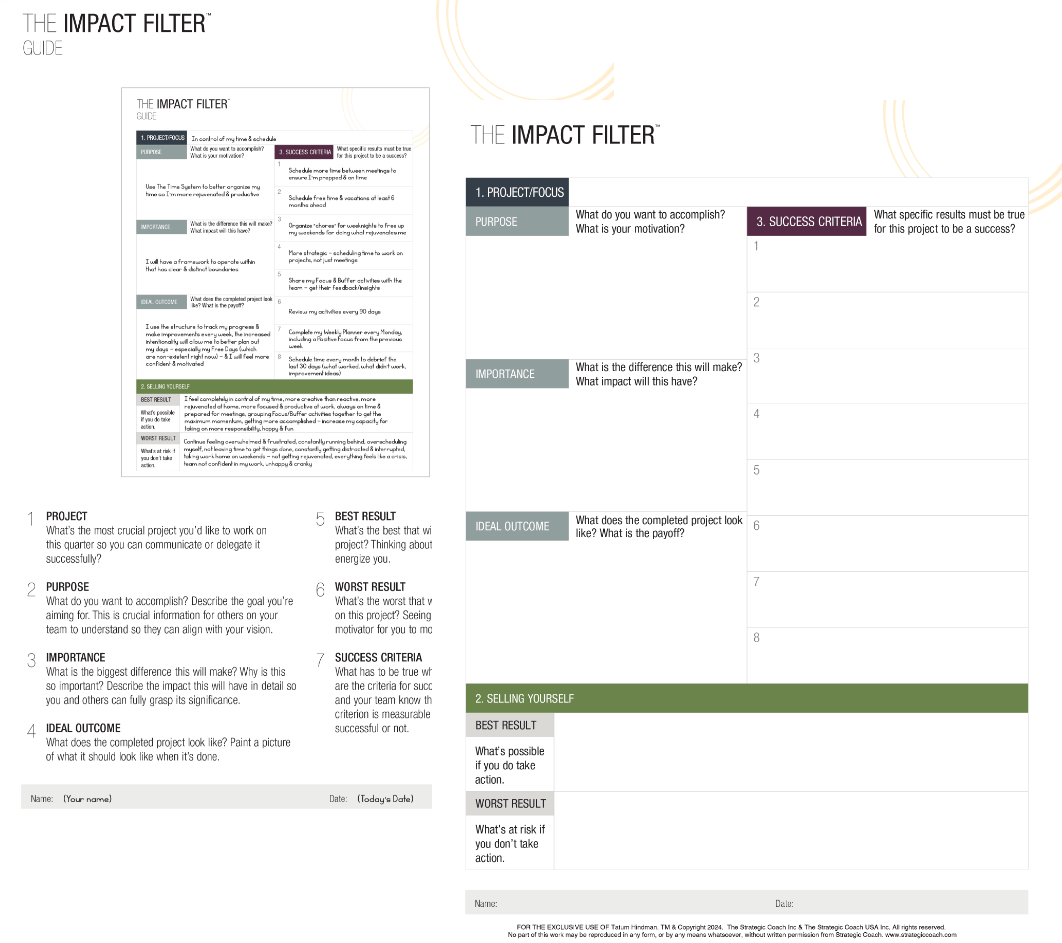

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.